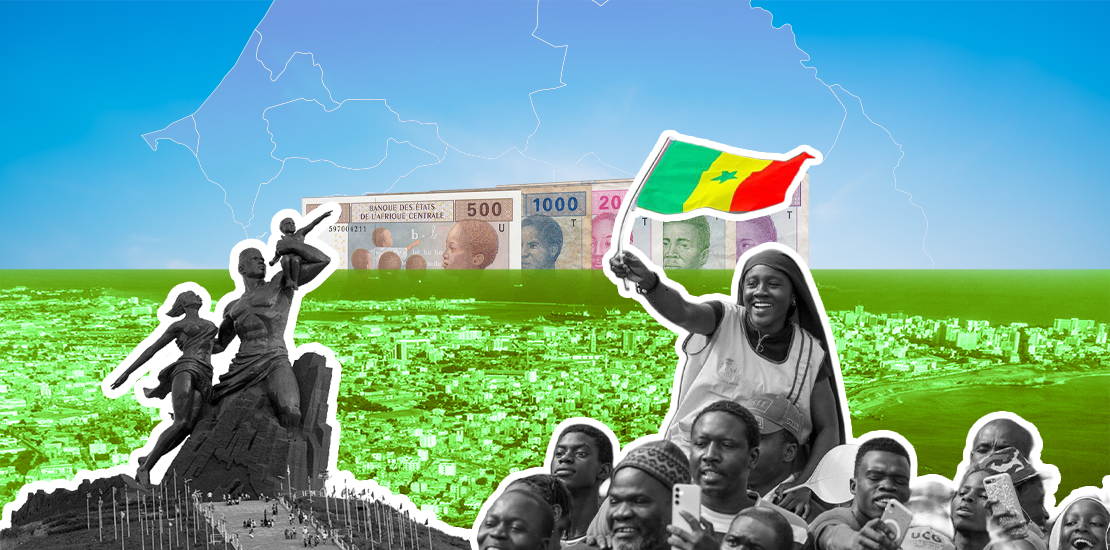

In Senegal, the issue of political financing remains sensitive and opaque. The major coalitions—Benno Bokk Yakaar yesterday, Yewwi Askan Wi and the alliances around Pastef today—live not just on rhetoric, but on financial flows that are difficult to trace. Between legal norms, informal practices, and community support, the architecture of financing escapes official radar. For economic players and international partners alike, mapping these circuits helps to better understand the balance of power between money and power, and to anticipate the risks of capture.

The starting point is a precise legal framework. Law No. 81-17 of May 6, 1981 requires each party to submit, by January 31, an annual financial account showing that its resources come solely from subscriptions, donations, and legacies from its members and national supporters, as well as profits from events. It prohibits "foreign subsidies" and provides for dissolution in the event of non-compliance. In practice, accounts are rarely filed, sanctions are non-existent, and no independent body exercises systematic control. Added to this is the absence of a law on public financing and spending ceilings: for the 2022 legislative elections, a deposit of 15 million CFA francs per list was added to high logistical expenses, with no requirement for banked campaign accounts.

In this context, the coalitions emphasize the three sources deemed legitimate: membership fees, national donations, and income from activities. They see this as proof of their "popular roots." Since 2021, Pastef has sought to systematize this logic with the "Nemmeeku Tour" fundraising program, presented as a model of "citizen self-financing" and credited with over 125 million CFA francs collected in a few hours, mainly through small contributions, including from the diaspora. The Yewwi Askan Wi coalition also used the Kopar Express platform to finance its campaigns. Online kitty campaigns and fundraising meetings have thus become part of the political repertoire, even though the law does not specify the status of these digital contributions or how they are to be monitored.

Behind these declared flows, a decisive part of the financing relies on relationships between politicians, senior civil servants, and business circles. The surveys describe a pattern in which the leader and a small circle negotiate the support of major operators or business leaders, sometimes via foundations or service contracts. Even within the staffs, the exact origin of resources often remains unknown. During the 2019 presidential election, the scale of the presidential coalition's resources, estimated at several billion CFA francs, illustrated this gray area between political funds, administrative budgets, and corporate contributions. In such a context, certain groups may "invest" simultaneously in several coalitions, less out of ideological conviction than to secure access to public contracts, favorable tax regimes, or sectoral regulations.

The role of foreign partners is theoretically limited by the ban on "foreign subsidies." In practice, many external players—governments, international organizations, and foundations—give priority to programs that favor institutions and civil society, rather than to financing coalitions. However, the absence of detailed rules on private donations and campaign spending fuels recurring suspicions: indirect support from multinationals via their subsidiaries, recourse to consultancy firms, sponsorship of events, relay by the diaspora. Scandals documented in other West African countries, where logistical or extractive groups have sought to influence elections, are fueling vigilance in Senegal. In the absence of mandatory reporting, these influences can only be detected through occasional signals and public controversy.

Sufi brotherhoods and their networks are another essential link in this landscape. Urban Dahiras, diaspora circles of disciples, and affiliated economic interest groups collect resources through subscriptions, tontines, and commercial activities. Their vocation is primarily religious and social, but these structures can also support a coalition on an ad hoc basis: providing buses, taking charge of meeting logistics, supporting candidates perceived as attentive to local interests. More than writing checks, influence is achieved through symbolic capital and the ability to influence the choices of thousands of followers, including entrepreneurs. However, the major brotherhoods are careful to preserve a form of pluralism, avoiding long-term alignment with a single camp.

For more than a decade, national commissions, researchers, and civil society organizations have been converging on one observation: the current triptych—a ban on foreign funding, a theoretical requirement for financial accounts, and a lack of regulation of campaign spending—is no longer sufficient. The avenues for reform are well known: public funding conditional on representativeness and compliance with accounting obligations, expenditure ceilings, bank-held campaign accounts, independent auditing, and publication of financial reports. The arrival in power of forces calling for transparency and self- -citizen financing has put this issue back at the top of the agenda. For coalitions and their economic partners alike, the challenge is to reduce the gray areas that fuel suspicions of capture, and to stabilize an environment where the rules of the game are legible and applicable to all.

Senegal

Senegal

Algeria

Algeria

Democratic Republic of Congo

Democratic Republic of Congo

FR

FR

EN

EN