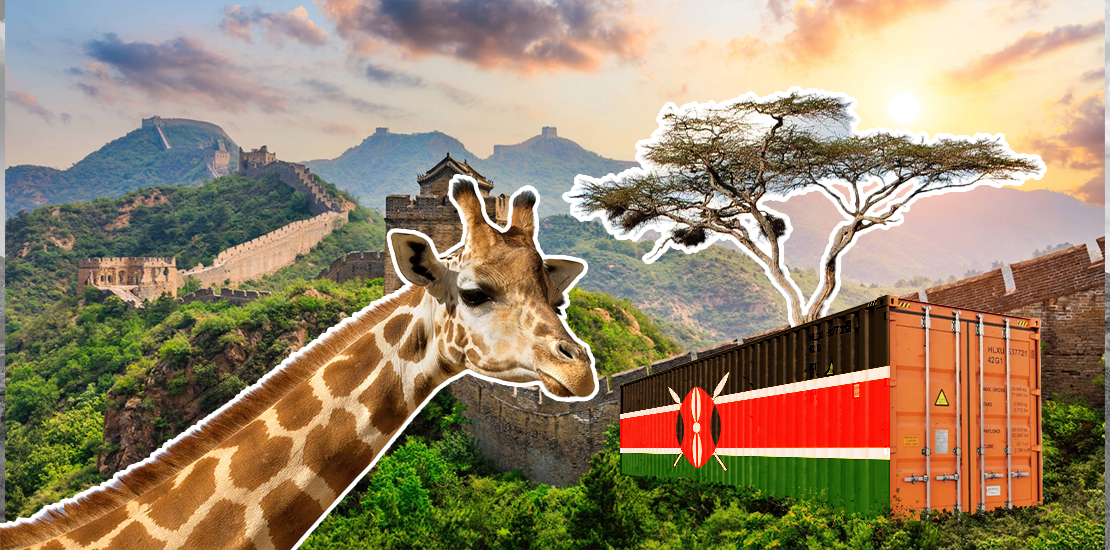

When the first Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) train left Mombasa for Nairobi in 2017, the Kenyan government saw it as a symbol of a country catching up: new rails, reduced travel times, the promise of a modern corridor into the interior of the continent. A few years later, this same line is the focus of concerns about the weight of debt contracted with China, the status of the port of Mombasa, and the state's ability to maintain control over its strategic infrastructure.

Kenya's public debt is now around two-thirds of GDP. It remains largely domestic, but the external share has increased significantly over the last decade. It is divided between multilateral institutions, private investors, and bilateral creditors. China is the largest creditor, even though, in terms of volume, World Bank loans now exceed those from Beijing. China's influence stems mainly from the type of projects it finances: heavy, visible infrastructure projects that are closely linked to the promise of growth.

The SGR illustrates this choice. Between 2014 and 2015, Nairobi secured a series of loans totaling around $5 billion from the Export-Import Bank of China for the Mombasa- Nairobi section and its extension to Naivasha. Part of this is concessional, with a low interest rate and long maturity. The rest is commercial, with a variable rate indexed to Libor and subject to commissions and export insurance. This arrangement seemed sustainable in a low interest rate environment, but the rapid rise in US rates and the depreciation of the shilling subsequently increased the real cost of the debt.

Operationally, the SGR has brought tangible gains: reduced travel times, increased freight capacity, a shift in road traffic to rail, and a consolidated northern corridor. However, public audits show that revenues still do not cover costs and debt servicing. To ease the pressure, the government renegotiated with Beijing and, in the fall of 2025, converted approximately $5 billion of SGR debt into yuan, a move expected to save more than $200 million in interest per year and limit currency risk.

The port of Mombasa is at the center of this architecture. In 2024, it handled more than 40 million tons of cargo and exceeded two million containers, confirming its status as a hub for Kenya and several landlocked countries in the region. It is also this centrality that made it, in 2018, the focus of a global debate on a possible Chinese "debt trap," after a letter from the auditor general was leaked suggesting that the Kenya Ports Authority had waived its sovereign immunity as collateral for SGR loans.

The idea of a "mortgaged" port then made the rounds in the media. However, a detailed examination of the contracts by research centers and lawyers has provided a more nuanced interpretation: the agreements do provide for collateralization mechanisms and a partial waiver of immunity, but there is no explicit clause transferring ownership of the port to Exim Bank in the event of default. The risk appears to be less that of a seizure of Mombasa than that of reduced negotiating leverage if the government were to find itself in financial difficulty.

These commitments have had very concrete effects. To secure SGR's revenues, the government introduced a dedicated tax on imports and required that the majority of containers unloaded in Mombasa be transported by rail. This obligation weakened road hauliers and fueled strong local resentment. The courts gradually restored shippers' freedom to choose their mode of transport, illustrating how an international contractual clause can reconfigure the economic balance of power around the port ( ).

In this context, the relationship between Nairobi and Beijing is becoming more cautious. Kenya is in talks with other partners, notably the United Arab Emirates, to extend the SGR to Uganda, and is relying more on multilateral institutions and markets to refinance its debt, while continuing to seek China's support for certain projects, such as a toll road between Mombasa and the interior of the country. The stated objective is to diversify sources of capital without giving up investments deemed essential for growth.

The sovereignty issues are clear. A growing debt burden limits the state's ability to finance public services and cushion social shocks. Commitments made to ensure the viability of the SGR have weighed on transport policy and port governance, directing flows and redistributing rent positions. More broadly, Kenya's dependence on foreign capital requires it to strike a delicate balance between its need for financing and its decision-making autonomy.

The Kenyan case shows the limitations of simplistic narratives, whether of a "debt trap" or entirely "win-win" cooperation. The SGR has strengthened Mombasa's position in regional trade, but it has also increased the financial burden on an already heavily indebted state and introduced contractual rules in port management that limit the authorities' room for maneuver. The challenge for Nairobi is not to break with China, but to renegotiate the terms of the relationship, make contracts more transparent, and place each project within an overall strategy, which is essential for preserving real sovereignty over its key infrastructure.

Kenya

Kenya

Algeria

Algeria

Democratic Republic of Congo

Democratic Republic of Congo

Senegal

Senegal

FR

FR

EN

EN