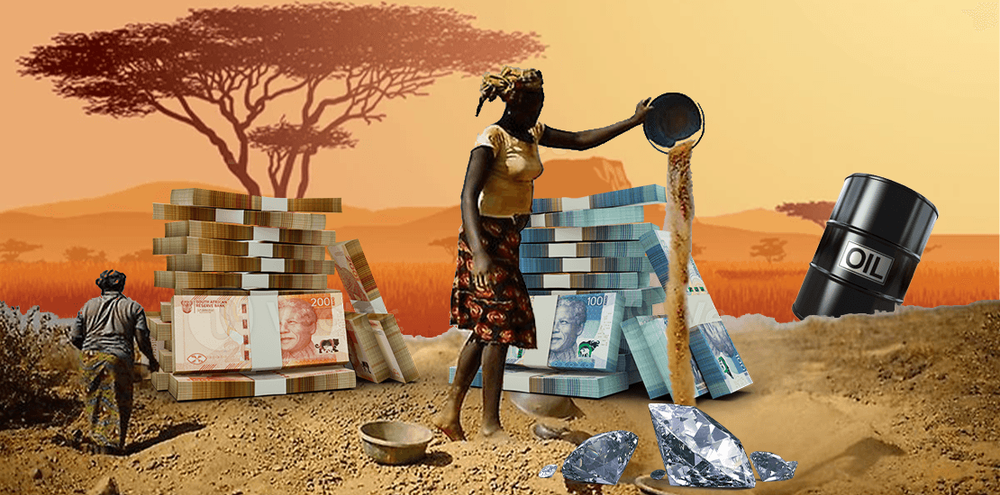

The face of African wealth evasion has changed. Far from Swiss secrecy, money now evaporates through apartments in Dubai, Mauritian holding companies, entities in the Seychelles or the Virgin Islands and, more recently, American trusts. On a continental scale, the bill is considerable: the United Nations estimates illicit financial flows at 88.6 billion dollars a year, or nearly 3.7% of African GDP. This figure, which rivals foreign aid envelopes, reflects a now well-established mechanism: arbitrating discrepancies in regulation, opacity and taxation to remove wealth from taxation and justice.

Dubai has established itself as a real estate safe haven. The "Dubai Unlocked" international investigation revealed a massive stock of property held by foreigners, including politically exposed African individuals, often through intermediary companies. Undercover tests have, in parallel, shown the acceptance of payments in cash or cryptocurrencies and lax controls on the origin of funds. For elites looking for a discreet home base, the appeal lies in speed of execution, competitive transaction costs and perceived high legal security: in a matter of days, a property becomes a safe haven, a mobilizable asset and, if need be, a recycling tool.

The typical scheme is simple. An intermediary sets up a company in an Emirates registration center (RAK ICC, JAFZA) or in a traditional offshore jurisdiction. The entity acquires the property, sometimes via an intra-group loan that blurs the traceability of flows. Rents or resales then flow back in the form of "dividends" or "reimbursements". Assets may be pledged to obtain cash presented as "own", while the real beneficiary remains hidden behind the legal screen. The depth of the real estate market enables rapid exits, accelerating capital turnover.

Offshore holding companies rationalize the holding of African assets other than real estate. Mauritius plays a key role here: 15% corporate tax, partial exemption schemes on certain mobile income, a vast network of tax treaties, legal stability and sophisticated financial services. Numerous private equity funds and pan-African groups have set up holdings in Mauritius to smooth taxation, secure legal arbitration and facilitate exits. There's a fine line between "aggressive" tax planning and tax evasion: the tool is legal, but it facilitates tax avoidance when the real economic flows and functions remain in Africa.

Switzerland has not disappeared; it has mutated. The automatic exchange of information, operational since 2017, has reduced the impunity of classic evasion. But the "Suisse Secrets" investigation uncovered thousands of accounts linked to high-risk clients and cumulative balances exceeding a hundred billion dollars at their peak, conclusions disputed by the bank concerned. Under regulatory pressure, some of these assets have been redeployed to Anglo-Saxon trust structures, notably American trusts (South Dakota, Delaware), which offer legal protection, vehicle longevity and discretion, while sometimes escaping the net of information exchange.

Above all, the gold chain has become a financial highway. Recent studies estimate that around 435 tonnes of African gold will have been smuggled out of the country by 2022, mostly to the Emirates, before being melted down and reinjected into the legal chain. Investigations in southern Africa have shown how networks of traders, transporters and public officials use the metal to recycle cash, circumvent capital controls and dilute the origin of funds. Gold has become an ideal vehicle for "money laundering through trade".

Who orchestrates this exodus? Three profiles dominate. Firstly, political and administrative elites or those close to them, anxious to protect themselves against changeover or the law. Secondly, captains of industry in cash-rich sectors (oil, mining, construction and public works, telecoms), well-versed in cross-border structuring and the fragmentation of value chains. Finally, a new generation of professionals (private bankers, business lawyers, chartered accountants, family offices) who standardize these structures for a regional clientele whose wealth is growing rapidly. All backed by an ecosystem of intermediaries capable of assembling companies, accounts, nominees and securities in a matter of weeks.

The macroeconomic impact is clear. The tax/GDP ratio in Africa is around 16%, compared with around 34% in the OECD. Every point that evaporates squeezes the budgetary margin, delays social investment and fuels debt dependency. Capital flight increases the risk premium, accentuates de facto dollarization and diverts credit to urban real estate at the expense of productive investment. In extractive economies, under-invoicing of exports and manipulation of transfer prices are eroding the base for corporate taxes and royalties, cutting into governments' ability to finance roads, hospitals and schools.

Counter-measures are progressing, but the game is not over. In 2023, the Emirates introduced a federal corporate tax (9%), supplemented by a minimum levy of 15% for very large groups, and strengthened registers of beneficial owners. Several African countries are rolling out their own registers and joining the automatic exchange of information. In October 2025, South Africa and Nigeria left the FATF's "grey list" following supervisory and transparency reforms. However, land transparency remains limited in Dubai, beneficiary registers are not always public in certain offshore jurisdictions, and data exploitation capabilities remain uneven on the African side.

What needs to be done? Three priorities stand out. First, make owners and transactions visible: interoperable registers, digital cadasters identifying beneficial owners, due diligence obligations genuinely applied to promoters, agents, notaries and lawyers, with extraterritorial sanctions against complicit professionals. Secondly, extend and exploit the exchange of information: cross-reference bank data, asset declarations, land registers and customs flows; automate discrepancy alerts; strengthen financial intelligence units and judicial cooperation. Finally, clean up the gold supply chains to dry up a major channel for money laundering.

In the short term, amnesties with strict conditions can speed up the return of assets, provided they are unique and credible. But the battle is being won above all on the "fiscal contract": digitizing collection, reducing costly exemptions, securing public spending and showing that taxation produces visible common goods. As long as the gap between State promise and reality remains yawning, the rational choice of the elites will be to place wealth beyond reach. Reclaiming wealth will require registers and algorithms as much as restoring trust.

Algeria

Algeria

Democratic Republic of Congo

Democratic Republic of Congo

Senegal

Senegal

FR

FR

EN

EN