The problem

Since the early 2000s, a significant proportion of Cameroon’s private capital has been escaping via offshore arrangements, shell companies, holdings, foreign accounts and trusts, blurring the identity of the actual beneficiaries. The issue goes beyond public morality: it affects tax mobilization, domestic investment and institutional confidence. The existence of an offshore structure is not illegal in itself; it is the opacity, and, where applicable, the illicit origin of the funds or tax fraud, that poses the problem.

Established facts

Major data leaks (Panama, Paradise, Pandora) have documented the use of “mailboxes” registered in the British Virgin Islands, the Seychelles or Hong Kong, interposing nominees between the real owner and his assets. Cameroon is a case in point: the “Offshore Leaks” database lists dozens of people and addresses linked to the country, revealing the recurrent use of intermediaries (trustees, nominee directors) and cascades of entities that dilute traceability. This architecture serves to segment ownership, shift flows and complicate any asset investigation.

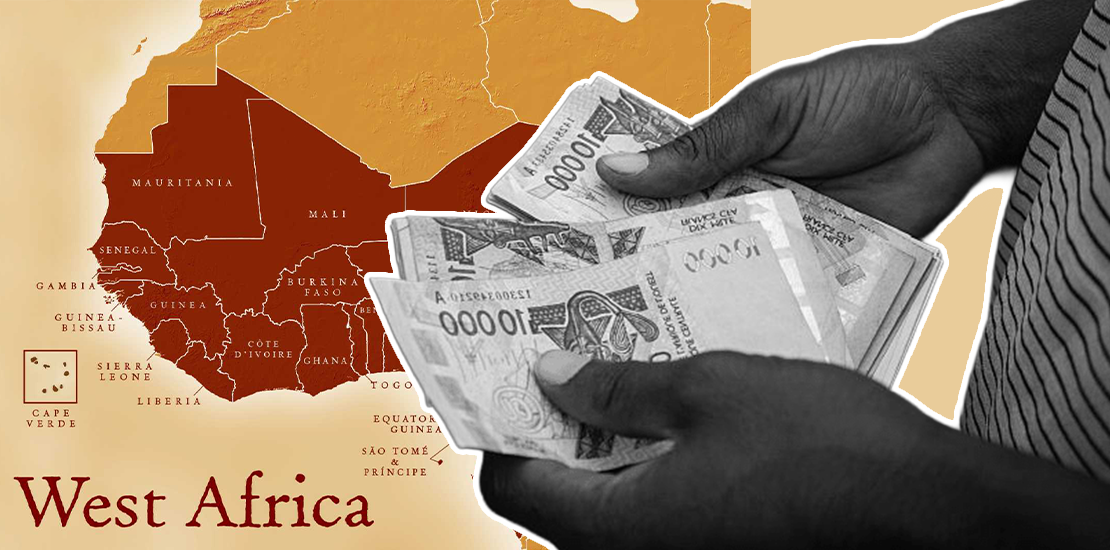

Preferred destinations

Three places come up again and again. Geneva, first and foremost: long protected by banking secrecy, Switzerland has long been a hub for the deposit of undeclared assets. The “SwissLeaks” revelations have shown the scale of private accounts linked to Africa, while reminding us that legitimate reasons exist (e.g. asset diversification); since 2017-2018, however, the automatic exchange of information has tightened the noose, without abolishing it for countries that do not participate. Paris, secondly: Parisian real estate, via non-trading real estate companies and holding companies, remains a classic vehicle for anchoring assets, in a market still criticized for its transparency shortcomings (identity of beneficial owners, uneven KYC checks among certain professionals). Lastly, over the past decade, Dubai has established itself as a hub for funds seeking stability, low taxation and real estate confidentiality. The “Dubai Unlocked” leaks illustrate the emirate’s role in the storage of international, including African, assets.

The mechanisms

Beyond holding companies and trusts, two channels are central:

- Trade misinvoicing, particularly in the extractive and forestry industries, which discreetly shifts margins abroad via biased transfer prices, discrepancies in declared export values and linked companies located in opaque jurisdictions.

- The stacking of entities (BVI → Dubai → Luxembourg, for example), with professional administrators, which fragments patrimonial indices between banks, registries and notaries and lengthens the probationary chain. At the end, the funds often materialize in prestige real estate (apartments, villas, service residences) that is easy to pledge, rent and resell.

- Putting things into perspective. Africa loses around $88-89 billion a year to illicit financial flows, an order of magnitude close to half of the continent’s MDG financing gap. Academic work on capital flight shows a robust link with institutional weakness, resource rents and over-indebtedness: the more governance is perceived as fragile, the greater the incentive to externalize private savings. Cameroon, a mixed economy and commodity exporter, is no exception to these dynamics – particularly in periods of fiscal tension and price volatility.

Actors, interests, strategies

– End-owners: securing savings outside domestic risk, optimizing tax burden, protecting inheritance.

– Intermediaries (law firms, trustees, real estate agents, private banks): provide “turnkey” structures and minimal compliance solutions.

– Host jurisdictions: attract legal flows and real estate buyers, support high-end service ecosystems.

– Home state: counter tax base erosion, preserve domestic savings for investment, demonstrate anti-corruption results.

In Europe, the closure or restriction of access to public registers of beneficial owners has created new grey areas for investigators and civil society.

Impact on the Cameroonian economy

Capital flight has a double scissor effect. On the one hand, it removes savings that could finance local industry, infrastructure or innovation. On the other hand, it reduces the tax effort borne by the wealthiest taxpayers, putting more pressure on consumption and SMEs. Cameroon’s tax burden remains below the African average: around 14% of GDP in 2022, compared with an average of around 16% for African countries covered by comparable statistics. On a microeconomic scale, the eviction of “patient” private investment is reflected in unfinished construction sites, maintenance delays and limited productivity. On a macro scale, it fuels recourse to public debt, which is itself sometimes poorly allocated, completing a vicious circle.

Public responses and limits

Cameroon has embarked on anti-corruption campaigns and introduced mandatory reporting of beneficial owners to tax authorities. In the extractive sector, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) has stimulated disclosure, although implementation remains bumpy and publicity of registers incomplete. At international level, the automatic exchange of information and OECD standards have reduced certain blind spots, but their effectiveness depends on the support of counterparties, the scope of data exchanged and the capacity of administrations to exploit them.

This would be a game-changer. Three levers stand out:

- Effective transparency of beneficial owners (interoperable register, controlled but operational access for press/NGOs, sanctions in the event of false declaration).

- Export value policing (customs and statistical support to detect price discrepancies, controls on related parties, cooperation with major trading centers).

- Real estate traceability in host hubs (mandatory declaration of beneficial ownership at the time of purchase, increased vigilance on the part of notaries/agents, cross-border information exchanges).

Ultimately, the challenge facing Cameroon’s offshore fortunes is not just to “catch fraudsters”, but to reconcile private savings with the public interest. As long as the combination of “opacity + capital mobility” remains more profitable than “investing at home”, the flight will continue. Conversely, credible transparency, predictable institutions and competitive domestic returns are the best antidotes. This is the price to pay if the money that sleeps in Geneva, is valued in Paris or sparkles in Dubai is to be put to work in Douala, Yaoundé or Garoua tomorrow.